Engineers working on Lake George in upstate New York believe they’re about to crack the code to protect water quality on bodies of water with developed shorelines … and onsite installers will play an important role in keeping these waterways clean and safe.

Sophisticated monitoring of underwater conditions — which includes diving to identify pollution-caused algae growth and a new IBM program placing data sensors throughout the lake — is showing early, promising results to identify environmental issues and correct failing septic systems.

Lake George is 32 miles long and 2.5 miles wide at its widest, is fed by surrounding mountain streams, and has a maximum depth of 190 feet. The headwaters lake has exceptional water quality overall, providing drinking water for thousands and with water clarity to depths of 35 to 40 feet.

But like the situation across much of North America, there is concern that water-quality conditions are changing. The lake is surrounded by roughly 6,000 septic systems, with an estimated two-thirds considered old or outdated. There is little oversight of these systems and no required routine maintenance or pumping interval established by the local government or the state of New York, not even time-of-sale inspections.

So local groups and Lake George Waterkeeper Chris Navitsky, an engineer who formerly designed onsite systems but now concentrates on clean-water advocacy, decided to take a deeper dive — literally — into the lake’s pollution situation.

“What we’ve seen is an increase in algae across the lake. It’s the canary in the coal mine,” Navitsky says. “That’s why we’re focused on it. The algae are telling us something.”

A group of 70 property owners around the small Dunham’s Bay formed the North Queensbury Wastewater District and began working with Navitsky and the FUND for Lake George to monitor the lake bottom in search of indicators of untreated sewage.

UNDERWATER INVESTIGATION

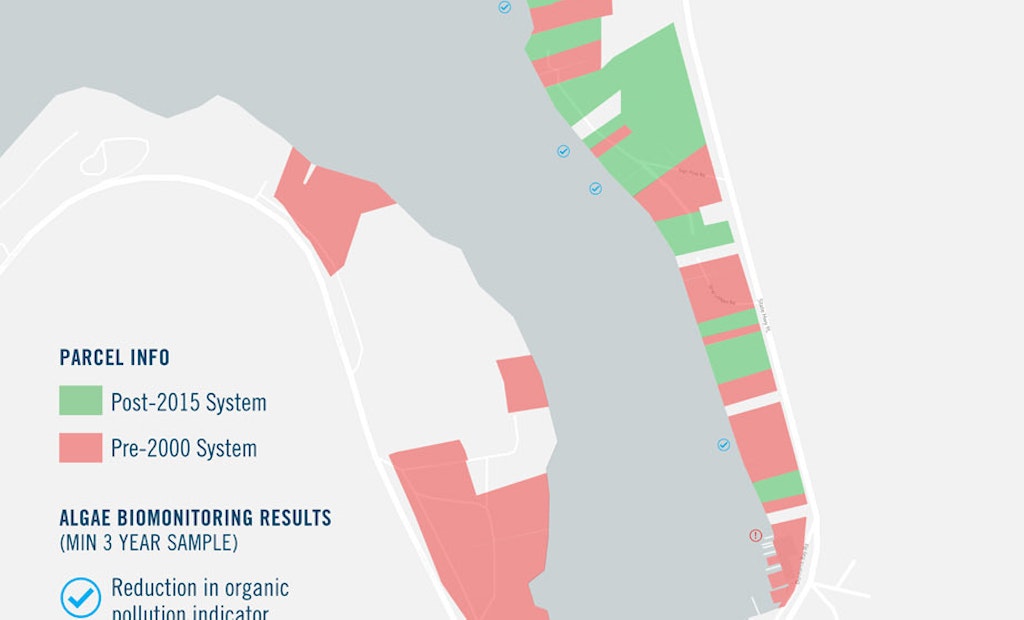

The Lake George Waterkeeper group began snorkeling near the shore, in 3 to 6 feet of water, using a syringe to take samples of algae growth from rocks and sand and having it analyzed to look for a type of algae (among 20-30 species typical in the lake) that grow in organic pollution conditions associated with human waste. They also take GPS readings, make notes on substrate and shoreline conditions, and take photographs.

When they identify algae that would point to possible failing septic systems, they don’t point fingers at homeowners, but allow the wastewater district to inform residents of the situation.

“I’ve always been cautious with the algae collection. What we may find doesn’t mean (the organic algae) is associated with a particular home’s system,” Navitsky says. “Because of fractures and fissures in the bedrock, the wastewater can trickle through the fissures and could go 200 feet north or south, taking the path of least resistance.”

Residents of Dunham’s Bay have been cooperative since the sampling started in 2014 … and it’s paid off in improved water quality. The Lake George Waterkeeper group offers matching grants of up to $8,000 per homeowner for system upgrades, and 11 of the 15 systems upgraded since the program started took advantage of the financial help.

Enhancements have cost between $14,000 and $20,000 and typically involve replacing septic tanks and adding an ATU component, as well as a UV unit downstream of the tank and before the drainfield. Regulators have usually allowed the existing drainfield to remain.

“The overall trend appears that the bay has improved, and we’ve seen a reduction of 25 percent in algae species associated with organic pollution,” Navitsky says.

PROGRAM EXPANSION

The inventory of septic systems in the 14-acre Dunham’s Bay is probably reflective of the rest of the lake properties, Navitsky says. Many of the cottages go back to the 1940s and were second homes or camps. Of the 70 properties, 21 percent had permitted systems with drawings on file at the town, 14 percent might have had a rudimentary sketch on file, and the rest were undocumented. Navitsky believes two-thirds of septic systems around the lake are undocumented.

That should be changing. As word spreads about the water-quality improvements on the small bay — as well as the grant program — more residents are asking to get involved. Receiving the Lake George Waterkeeper money comes with some stipulations that will help in the overall inventory of lake systems, Navitsky explains.

Lake area owners can petition the local town to form a wastewater district to tap into available monitoring and matching grants as septic system upgrades become necessary. To be part of a wastewater district, homeowners must agree to:

- Municipal oversight and management

- Professionally engineered septic system plans

- Town approval of wastewater system improvements

- Implementing water conservation fixtures to reduce flows

- System inspections and service contracts for advanced systems.

To bolster interest in the program, local groups organized a Septic Summit education event in 2017. Decentralized wastewater manufacturers came to showcase their technologies, and designers and installers were offered continuing education credits through the state to attend and learn.

SMART LAKE

Beyond the work in Dunham’s Bay, the Jefferson Project of IBM Research, the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, and the FUND for Lake George will make this body of water “the smartest lake in the world,” Navitsky says. A collection of 50 computer sensors have been installed throughout the watershed to collect data to show water runoff patterns, how the water enters and circulates in the lake, and how weather patterns and precipitation impact the lake.

“It’s quite amazing what this project is doing. It’s groundbreaking,” Navitsky says. “The sensors talk to each other and sense weather events coming in. The deployed sensors will be used to predict what stressors can do to an ecosystem and use modeling to predict into the future. The sensors can determine that the replacement programs we’ve implemented and funded are clearing up water quality the way we think algae changes are showing.”

The IBM program has been developing at the same time as the algae identification in Dunham’s Bay and is expected to produce results in a year or two, he says.

ONSITE INDUSTRY IS KEY

Knowledge of water-quality issues and maintenance and care of septic systems are continuing to improve, but there is much more to do, Navitsky says. And wastewater professionals in the region — installers and pumpers — are poised to help out as issues are identified and systems need maintenance and upgrading, he says.

“The most important thing anybody can do is pump your system out every two to three years. That’s how we gain 80 percent of the knowledge on the condition of our systems,” he says, noting the opportunity to inspect baffles, filters, looking for cracks in tanks, the drainfield. That pumpouts are not required, “is surprising, but it is what it is. That’s why we’re trying to promote this. You’d think common sense would fall into place and you should require pumpouts.”