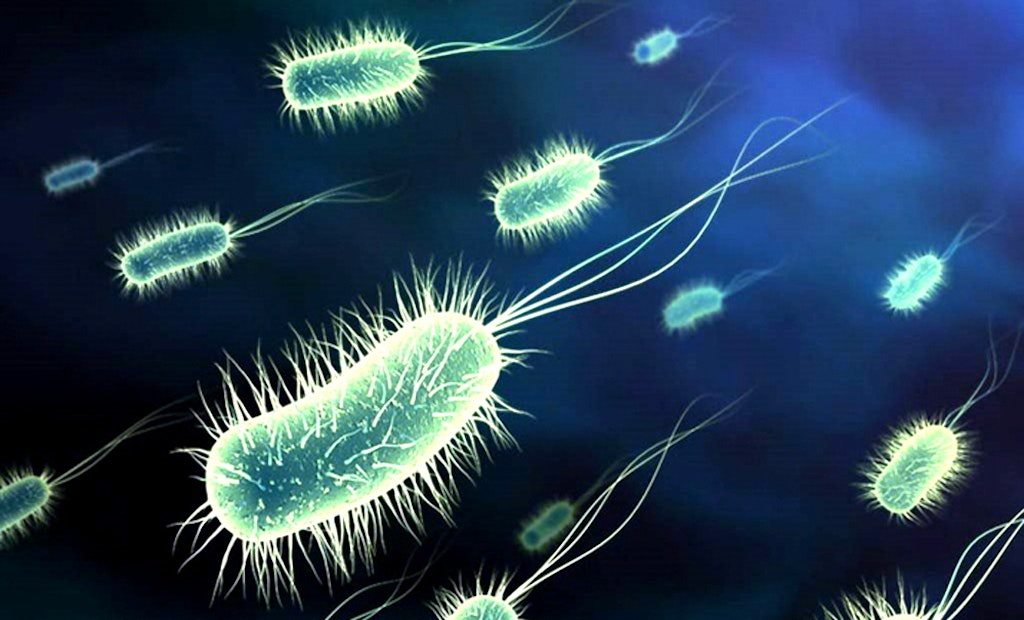

Removing pathogens is the most critical part of wastewater treatment. Pathogens are organisms that cause disease; they include viruses, protozoa and bacteria. Examples in wastewater include salmonella, Vibrio cholera, Entamoeba histolytica, and cryptosporidium, although almost...

This article is part of the series: An Installer's Guide to Wastewater Characteristics

- The Installer’s Guide to BOD5

- An Installer’s Guide to Total Suspended Solids

- An Installer’s Guide to COD

- An Installer’s Guide to FOG

- An Installer’s Guide to Phosphorus

- An Installer’s Guide to Wastewater Pathogens

- An Installer’s Guide to Nitrogen