Interested in Education/Training?

Get Education/Training articles, news and videos right in your inbox! Sign up now.

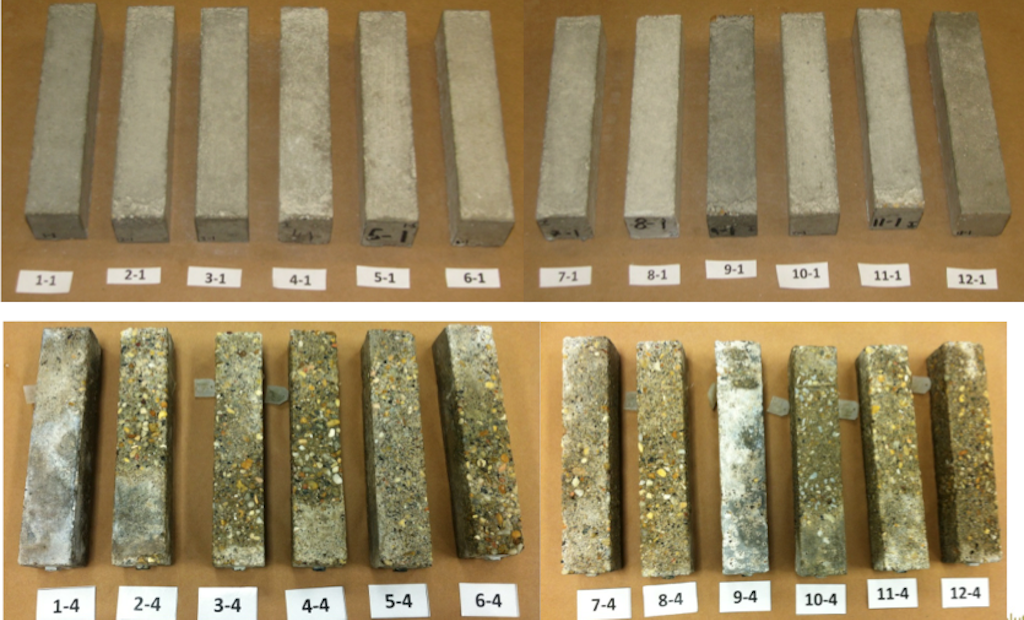

Education/Training + Get AlertsAfter a few years of study, researchers sponsored by the National Precast Concrete Association have a grip on how microorganisms can combine with specific environmental conditions inside tanks to deteriorate concrete. You know this by other words: microbiological induced corrosion, or MIC.

The work is not nearly finished, but scientists and engineers have provided some knowledge that installers and inspectors can put to use in the field when they suspect that bacteria are deteriorating a septic tank. The most recent findings were presented in February by Claude Goguen, P.E., director of sustainability and technical education for the National Precast Concrete Association, in a seminar at the Water & Wastewater Equipment Treatment & Transport (WWETT) Show.

Phase 1 findings

The first part of the study was all laboratory work. “To understand an issue you first must understand the process,” says Phillip Cutler, the association’s director of quality assurance programs and its liaison to the NPCA MIC task force.

But before entering their labs, scientists looked for past research and found some studies contradicted each other, and not many of the studies focused on what happens in onsite installations. They went on to replicate MIC in a lab. It’s a difficult and very dangerous process to replicate because the bacteria involved are fussy about the conditions they grow in.

“Conditions in the laboratory or the field have to be just right in terms of temperature and in terms of moisture level. We believe this work was groundbreaking for just understanding the process. Now we can start investigating how to disrupt that chain of events,” Cutler says.

For MIC to occur, three stages must occur. The first, carbonation, occurs naturally when some concrete constituents react with carbon dioxide in the air. When it comes out of a form, concrete is naturally alkaline with a pH of 11 or higher.

As the carbon dioxide reacts with calcium hydroxide in the concrete, the pH of the concrete surface drops very gradually. If the pH falls to about 9 and thiobacilli grow, the second stage can begin. These microorganisms live and grow in a film that develops on the surface of the concrete. They can produce sulfuric acid after feeding on the hydrogen sulfide gas produced by other bacteria in the wastewater. As the surface of the concrete becomes more acidic, other species of thiobacilli that produce even more acid can begin growing. This is the third stage where large quantities of acid damage the surface of the concrete to produce MIC.

Scattered but a concern

MIC doesn’t happen very frequently but grabs attention when it does, Cutler says. There seems to be some concentration in the upper Midwest: in parts of Wisconsin, Indiana and Ohio. There are scattered reports of MIC from other parts of the country, and while there aren’t enough reports to show a definite pattern and most tanks will last a long time, MIC is a concern, he says.

MIC can be difficult to recognize in septic tanks. When it is present there is a white, chalky coating on the inside of a tank, like wet drywall, Goguen says. But that coating does not always signify MIC, and there is no laboratory test to say MIC is or is not present.

For the moment, diagnosing MIC depends on the eyes of inspectors, installers and technicians, Cutler says. “They’re likely the most qualified to recognize a strange-looking phenomenon because anybody who does a lot of maintenance is going to see a lot of tanks. If they look at a tank and see something that doesn’t look right, it probably isn’t right.”

Consulting with the precaster can also help, Goguen says. It’s difficult to diagnose MIC based on an email or photo, but the NPCA is willing to help, too. “We have at our disposal a lot of experts in the wastewater field. Usually I’ll share information that comes in and get some opinion about what may be happening inside a tank.”

Phase 2

The next research step is to go out in the field, and that’s already underway, Cutler says. NPCA members and staff are going to areas in Wisconsin, Indiana and Ohio where reports of MIC are frequent. They install sensors inside tanks, then watch the environment to see what happens. They’re doing the same in other parts of the country where MIC reports are not common. Cutler says he doesn’t know how long this phase will take.

“There are so many factors that can potentially affect what’s happening inside a tank that we knew we wouldn’t solve this problem in a year. It’s a big topic, and we have to take it one step at a time,” Goguen says. But when this research is done, scientists should be able to give some advice about where to interfere in the chain of events that can lead to MIC, perhaps by altering the surface of the concrete somehow, or by changing the environment inside tanks.

What to do now

Even if the research isn’t done, installers can take steps now to reduce the likelihood of MIC. It starts with a good mix, Goguen says.

“Very generally speaking, quality will enhance durability. That alone may be enough for some environments. The producer may also have some additional measures for aggressive environments, such as additives and coatings. A low-quality tank will be vulnerable to other issues, and not just MIC. The first step is to ask the producer. Producers are the experts in precast concrete. They understand how their product is manufactured to withstand certain conditions.”

Goguen (cgoguen@precast.org) and Cutler (Pcutler@precast.org) say they welcome reports of possible MIC or questions about materials. “We’d be happy to help within our capacity,” Goguen says.