Interested in Systems/ATUs?

Get Systems/ATUs articles, news and videos right in your inbox! Sign up now.

Systems/ATUs + Get AlertsSlaughterhouse wastewater is not covered under most state septic regulations, as septic system sizing is based on research of typical flows and wastewater characteristics from domestic residences.

For small slaughtering facilities a decentralized onsite option for treating its wastewater may be the most cost-effective — particularly if connection to a wastewater treatment plant is not feasible.

A septic system receiving slaughterhouse waste is considered by the Environmental Protection Agency to be a Class V injection well system. Depending on the requirements of your state, county and/or local authorities, wastewater can be treated in various ways. Keep in mind that there is no one “best” wastewater treatment system. Different processors have different needs. Finding the right wastewater treatment system for the facility will depend on a number of variables.

1. First you will need to determine what type of activities will occur at the facility:

- Slaughtering

- Cut and wrap

- Value-added processing

- Sales room

- Worker showers and/or laundry.

Each of these activities will add additional loading to the system.

2. Which species are being processed: hogs, sheep, goats, poultry, wild game, etc.

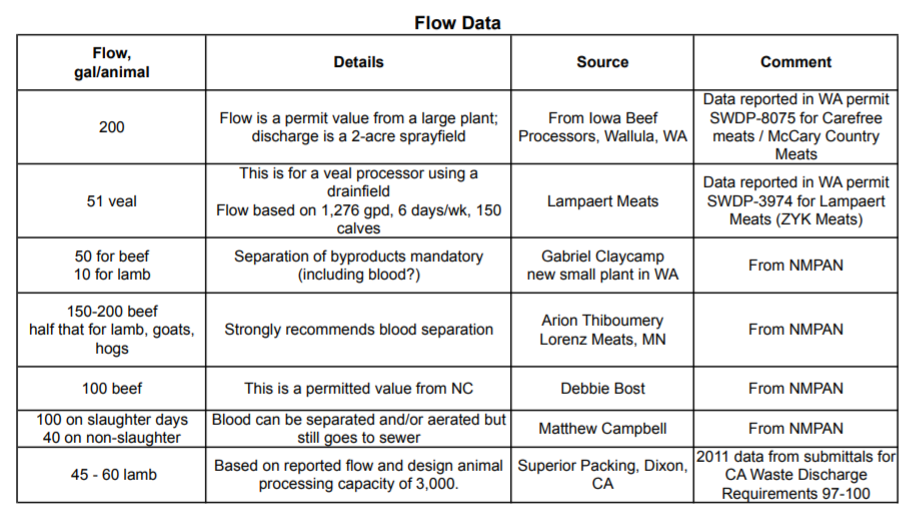

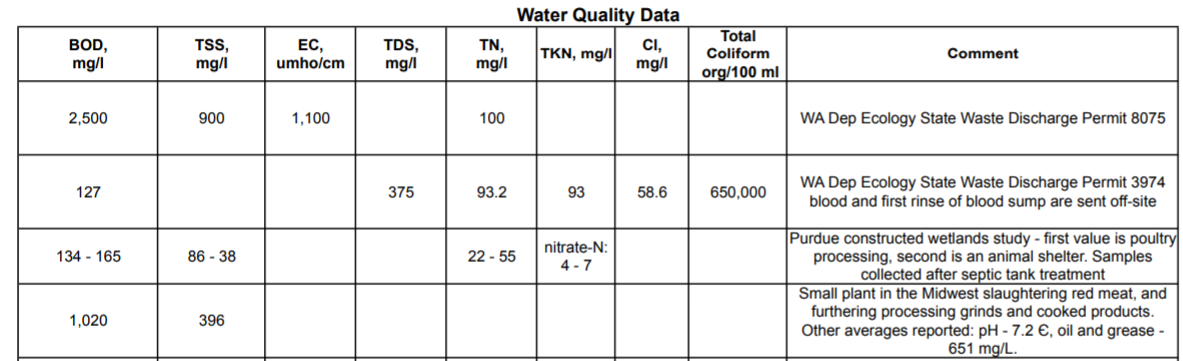

3. Estimate or measure the volume of wastewater output each day and wastewater characteristics. Measure or estimate the pH, total suspended solids, biological oxygen demand and FOG levels. For existing facilities, flow measurements should always be obtained. The tables below show flow estimates and wastewater characteristics that were gathered by Niche Meat Processor Assistance. It should also be determined if processing will be consistent or seasonal in nature.

Option 1: In general, if it is possible to connect to a municipal wastewater treatment plant, this is often a good option. If the facility is located within reach of these services, it will likely be worth paying the initial connection fees and monthly sewer costs rather than building and managing a small onsite wastewater treatment system. Before this decision is made, the facility should contact the local public works or municipal wastewater treatment facility to find out about connection fees and estimated monthly charges. With smaller towns or undersized wastewater treatment plants, the additional loading from a larger slaughterhouse may be a challenge.

Option 2: For smaller facilities installing a holding tank that is pumped may be an option. The holding tank waste could be land-applied or taken to a wastewater treatment plant. This is also a good option for phased growth where the system can start as a holding tank and once the business is more established an onsite wastewater treatment system can be installed. The holding tank should have an alarm to indicate when it is 75 percent full.

Option 3: A typical/conventional septic system with only a septic tank and drainfield will not work for meat processing plants because of the high levels of BOD, TSS and FOG in the wastewater. If it is a larger facility, building an anaerobic digester, pond or lagoon system may be a good option, but for smaller facilities, a septic system with advanced treatment could be a good solution. The most likely design solution would be installation of an aerobic treatment unit after settling and oil and grease removal in septic tanks. With high-strength wastewater, flow equalization with time dosing should be considered, and flow monitoring is essential for proper management. Other recommendations include:

- It is best to separate the animal processing wastewater from human domestic wastewater for bathrooms, showers and laundry. The domestic wastewater will need to meet all the local/state septic regulations where the remaining wastewater will likely be governed by an industrial- or agricultural-related program.

- Use of cleaning chemicals should be kept to a minimum. Septic systems can deal with small amounts of cleaning chemicals, but if the amount is above typical domestic usage, system performance may be impacted.

- If animals are killed in the facility, all blood should be caught separately and either used, rendered or taken to a treatment facility.

- All solid material should be dealt with as a solid waste. Fine grates should be put on all floor and sink drains to catch any small particles and hair.

- A commercial-size effluent filter (designed for high-strength waste) should be placed on the outlet of the last septic tank. A manhole should be located over this filter, as there will be a need for frequent maintenance and cleaning.

- A maintenance contract should be in place with a licensed onsite professional to assure the proper operation and maintenance of the treatment system.

After treatment, the remaining item for consideration is where the dispersal will occur. Depending on the quality of the effluent, size and climate, irrigation may be an option; in some areas, a subsurface drainfield may be a better option.

About the author: Sara Heger, Ph.D., is an engineer, researcher and instructor in the Onsite Sewage Treatment Program in the Water Resources Center at the University of Minnesota. She presents at many local and national training events regarding the design, installation, and management of septic systems and related research. Heger is education chair of the Minnesota Onsite Wastewater Association and the National Onsite Wastewater Recycling Association, and she serves on the NSF International Committee on Wastewater Treatment Systems. Ask Heger questions about septic system maintenance and operation by sending an email to kim.peterson@colepublishing.com.